Information Science

For Software Traceability & Retrieval

This blog proposes a data science analysis that contributes to inform decision making in software engineering teams about traceability & retrieval of software artifacts. More specifically, the goal of this document is to articulate cases where the information captured in these artifacts might make it difficult for a developer to be able to effectively trace them to various locations in source code where they are implemented. For example, consider a situation where a development team needs to modify the XXX system based on an incoming new requirement. How should the developers proceed if we assume they are not familiar with all the components of the system or codebase? They probably will start by tracing functionality between previous requirements and the code by reading the associated documentation (e.g. code comments etc.). However, what if the descriptions in the requirements artifacts are poorly written? Or what if certain areas of the source code are not completely documented or use obscure identifiers? Likely, the traceability process that a developer would undertake to understand the impact of the new requirement would be cumbersome and inefficient. We use information science and automated traceability to identify potential artifacts that might negatively contribute to the understandability of a given system. We briefly discuss an overview of our findings from this analysis below.

For the XXX system we found that oftentimes, pull request comments and the associated source code often contain different information. That is, it is very likely that the pull request comments and source code and its comments are describing disparate information. This is based on an information theoretic analysis that carries a 95% confidence which signals that pull requests contain [3.42 ± 0.02] bits and source code contains [5.91 ± 0.01] bits of information respectively. Such an imbalance of information should be avoided as it suggests that the code changes might not accurately capture the information content of the pull request. What could high quality mean in this context? A well-written pull request is an artifact that a software engineer can easily trace on the source code documentation. This report lists concrete examples in the last section where potential links suffer from imbalance. This current automated analysis can be used to detect these instances of information mismatch, and our planned follow up work will attempt to make semantically meaningful suggestions for revisions to improve the documentation.

In a sample of 21,312 potential trace links (i.e., from pull request comments to python files), the information loss went from about 2.68 up to 2.72 bits among artifacts for a 95% confidence interval. This result implies that, on average, 84.11% of the information content in the pull request comments cannot be traced back to the source code or it’s comments. This information loss is likely occurring due to mismatches the source artifacts have tokens that cannot be found in the target artifacts. Additionally, the information noise (or content that should not be in the source code) went from about 0.21 up to 0.22 bits, which indicates that no suspicious information was found in the code.

In general, we recommend examining these imbalanced links, or information discrepancies, between pull requests and source code in order to design a refactoring strategy oriented toward reducing the loss and augmenting the mutual information among the software documentation. Bear in mind that the level of mutual information is around 3.21 bits with an error of 0.02 for a confidence of 95%. An ideal range of mutual information may vary according to the system. However, managers should avoid lower values in the mutual information range. Our full blog report below contains additional information as well as the technical details of our techniques.

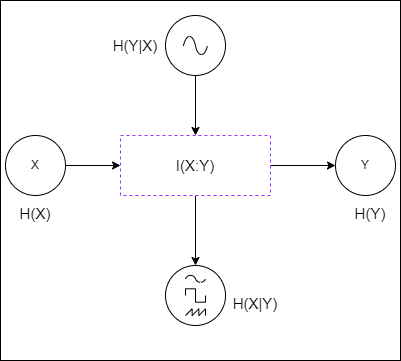

A note about information theory: Information can be transmitted by copy [Tc] or transformation [Ts] and measured by Mutual Information. However, some studies have determined that the MI does not distinguish between a scenario where the target artifact is a copy of the source artifact versus another scenario where the target is a systematically transformed version of the source artifact. Since the minimal information unit in software artifacts is a set of tokens, the information within the source artifact X can be transmitted by copy if the same amount of tokens are found in the target artifact Y. While the source information X can be transmitted by transformation if the target artifact suffers a modification in its syntax or semantics. Nonetheless information can be transmitted in both ways in software systems, we are assuming that the function f(X) is a “copy” process that uses the source information and produces an information target Y. The outcomes generated are software artifacts such as source code, test cases, or design diagrams. Addressing the problem of transformation requires further investigation in applied Information Theory for SE. Moreover, this research is contributing to formalize information measures for software text artifacts and bridge the gap between information theory and unsupervised learning for traceability.

1. Introduction

In this exploratory blog report, we address the problem of information transmission in software traceability. Traceability is the study of semantic relationships among textual artifacts. These semantic relationships are relevant to facilitate code comprehension, compliance validation, security tracking, and change impact analysis. Usually, information retrieval techniques (e.g., TF-IDF, LSA, or LDA) have been employed to mathematically represent high level (i.e., requirements) and low level (i.e., source code) software artifacts in compressed tensors. These tensors are learned in an unsupervised setting and employed to calculate a distance (e.g., euclidean, cosine, or Word Mover’s) between two artifacts in distinct vector spaces. The distance defines how semantically close two artifacts are between each other.

Unfortunately, information retrieval techniques cannot always guarantee that any predicted trace link is reliable. Because a data-dependent logical gap exists among different software artifacts, traceability is a difficult and error prone task. Information Retrieval and, in general, Machine Learning focus their attention on finding patterns in data. Data is the central aspect of learning theory. If the data are insufficient or poorly treated, then this is going to be reflected in the effectiveness of the learning algorithms. The traceability algorithms rely on patterns that might not exist in the given (or exposed) artifacts. Consequently, bridging the logical gap is unfeasible. There remains a need for an efficient statistical approach that quantifies how reliable trace links are.

Theoretically, software requirements should be amenable to being translated into multiple forms of information such as source code, test cases, or design artifacts. Thus, we refer to these requirements or any initial/raw form of information as the source artifacts. Conversely, the information that is a product of a transformation or alteration is considered a target artifact. In the software engineering context, a transformation could be any action that a software engineer applies from those requirements. For instance, implementing a requirement can be seen as a way of translating information from the requirements to the source code.

The approach we have used in this study aims to calculate a set of information measures to complement and explain the limitations of semantic traceability techniques. Understanding such limitations (or bounds) will allow us to assess how well traceability algorithms work for a given software project. Numerous experiments have established that studying the manifold of information measures might help us to detect critical points on the artifacts. These critical points are potential missed documentation or repetitive tokens that need to be refactored to enhance the effectiveness of traceability algorithms. The following list poses a set of information measures and exemplifies their usefulness in software traceability:

- Self-Information of source artifacts I(X). This is the entropy of a set of source artifacts or requirements. Entropy in information theory is the amount of information encoded in a given artifact. The information is measured in terms of bits (B). The following example shows the entropy of the XXX pull request with id 128:

- Pull Request Content: “B dtimeout”

- I(X=PR-128): 0.0 B

- Interpretation: Generally, having a pull request with few (and repetitive) tokens (words) impacts negatively the self-information value. This metric is useful to measure the content of information in the source. If we track the information content, we can explain why a traceability occurs.

- Self-Information of target artifacts I(Y). This is the entropy of a set of target artifacts or source code. Intuitively, self-information of a target artifact is the same formula as the entropy for a source artifact. The only difference is that the target artifacts are often source code. The following example shows the entropy for the XXX source code file with path xxx-python-common/xxx_python_common/fireException.py’:

- Source Content: “import sys\r\nimport traceback\r\n\r\n\r\ndef fireException(message):\r\n try:\r\n with open(“buddy_script_error.txt”, “w”) as file:\r\n file.write(str(message))\r\n print(message)\r\n traceback.print_exc()\r\n sys.exit(-1)\r\n except IOError:\r\n traceback.print_exc()\r\n sys.exit(-1)\r\n”

- I(Y=fireExcpetion.py): 4.16 B

- Interpretation: The amount of information that is encompassed in the fireException.py file required 4.16 B. Notice that the source content is more diverse than PR-128. This metric is useful when you compare it with the self-information of a source artifact. It helps us to measure imbalance information in a given trace link.

-

Mutual Information I(X:Y). This is the amount of information that X can see of Y and the amount of information that Y can see of X. That is, MI quantifies the information that two artifacts hold in common or the amount of information transmitted from a source to a target. For example, the trace link {PR-256 ➝ binary_scan_func.py} has a MI of 6.38B, which corresponds to the maximum entropy found in the dataset. This value suggests that the content in source artifacts overlaps a large portion of the content in the target artifact. However, the potential link {PR-56 ➝ binary_scan_func.py} has the same MI as the previous link but it is not a real link according to the ground truth. If we observe the case study 0 (see last section), we notice that both PR-56 and PR-256 have the maximum self-information observed in XXX as well as the artifact binary_scan_func.py. The mutual information analysis is telling us that the potential link {PR-56 ➝ binary_scan_func.py} could be an information link not considered by the ground truth.

-

Information Loss I(X|Y). This is the amount of information that comes into the channel but it does not come out (or never depicted in the target). That is, source code files that have not been implemented in the system yet (or probably poorly documented requirements/source code). For instance, the links {PR-240 ➝ binary_scan_func.py}, {PR-240 ➝ security_results_push_func.py}, and {PR-168 ➝ auth_utility.py} have a loss of 6.51B, 6.48B, and 6.3B respectively. All the pull requests have in common the low information content in their files. Therefore, it seems that the PRs were not well described.

- Information Noise I(Y|X). This is the amount of information that comes out (or found in the target) but it does not come in (or never depicted in the source). That is, information implemented by a developer that was never mentioned in the issues or requirements. For instance, the links ${PR-194 ➝ __init__.py}$, ${PR-177 ➝ fireException.py}$, and ${PR-56 ➝ setup.py}$ have a noise of 1.83B, 1.81B, and 1.55B respectively. All the source code files have in common the low information content since these artifacts are config files, which makes more sense. The question here would be: Why is there a link between a pull request and a config file?

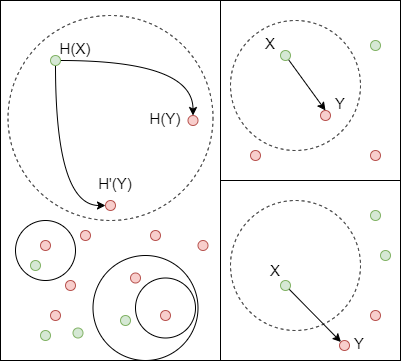

Additionally, we introduce the concept of Minimum Shared of Information for entropy (MSI_I) and extropy (MSI_X). The Minimum Shared information is different from the Mutual information because MSI just considers the minimum overlapping of tokens between two artifacts to compute an entropy. For instance, Artifact A has these token counts A_{for:14, if:3, return:10} and artifact B has these token counts B_{for:10, if:0, return:20}. The minimum shared vector would be min(A,B) or AB_{for:10,if:0,return:10}. This shared vector is a probability distribution. With that distribution, we are able to compute both minimum entropy and extropy. This minimum entropy is useful for detecting null shared vectors or artifacts whose tokens are completely opposed.

- Minimum Shared of Information for Entropy. This is the minimum number of tokens shared between the source and target set represented as entropy. In total, there are 5417 potential links for XXX whose shared vector is null. From those potential links, 68 are actually links by the ground truth. Some examples:

Examples of PR-295: {PR-295 ➝ psb_mapping.py}, {PR-285 ➝ binaryScan.py}, {PR-285 ➝ test_BinaryScan.py}

Examples of PR-241: {PR-241 ➝ csbcicd_report/csbcicd_func.py}, {PR-241 ➝ third_party/binary_scan_func.py}, {PR-241 ➝ csbcicdReport/test_csbcicd_func.py}

The core idea of using Information Measures with Software Traceability is to determine and quantify the boundaries of the effectiveness of Unsupervised Techniques. In other words, we want to demonstrate that traceability data is insufficient to derive a trace pattern if the information measures are not in optimal ranges. Hence, information retrieval techniques are limited approaches to produce reliable traceability links. However, we can also determine to what extent is the information lost during the transmission process {Pull Request ➝ Source Code} as well as to what extent is the information noise in target artifacts. The information loss and noise could be relevant for security purposes (i.e., why a given piece of source code is not covered by the requirements?).

2. Empirical Evaluation Setup

The results presented in this section are a product of the optimal configuration of IR techniques for software traceability reached with baseline datasets (LibEst, iTrust, eTour, EBT, and SMOS). This configuration is defined as follows: conventional preprocessing, which includes stemming, camel case splitting, and stop words removal. The traceability arrow is from “issues’’ to “source code” (issue2src). The vectorization technique employed is skip gram (word2vec) and paragraph vector bag of words (pv-bow) (doc2vec). The pretraining was performed with the java and python code search net dataset. The embedding size was 500 and the number of epochs were 20 for each model.

The data science information pipeline is composed of 2 analyses and 1 chapter for case studies. The 2 analyses are:

- Exploratory Data Analysis for Interpreting Traceability. The goal of this section is to measure the set of information measures and summarize the results in probability distributions. The data is also analyzed according to the ground truth and variable correlations. This exploration allows us to interpret how well an unsupervised technique for traceability will perform.

- Supervised Evaluation. The goal of this section is to show the effectiveness of the unsupervised techniques and their limitations due to information measures.

3. Exploratory Data Analysis for Interpreting Traceability

Exploratory Data Analysis is an exhaustive search of patterns in data with an specific goal in mind. For this report, our goal is to use information measures to describe and interpret the effectiveness of unsupervised traceability techniques. This section introduces 3 explorations:

- Manifold of Information Measures. The purpose of this exploration is to determine the probability distribution of each entropy and similarity metric. We have some assumptions about how we expect these distributions to be. For instance, similarity distributions should be bimodal since we want to observe a link and a non-link. If our assumptions do not match the expected distribution, then we can assess the quality of the technique.

- Manifold of Information Measures by Ground truth. The purpose of this exploration is to group each entropy and similarity metric by a given ground truth. The division of data by the ground truth allows us to determine the quality of the prediction for similarity metrics. Additionally, it also allows us to describe how good the ground truth is since we are measuring the information transmission between source and target artifacts.

- Scatter Matrix for Information Measures. The purpose of this exploration is to find correlations between information theory metrics and unsupervised similarities. These correlations help us to explain the traceability behaviour from information transmission for a given dataset.

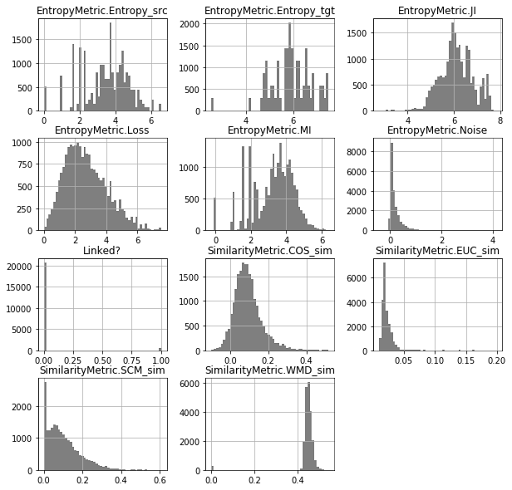

3.1 EDA1: Manifold of Information Measures

The following manifold depicts the distribution of each information variable. We can observe that the self-information of the source artifacts (or issues) is on average [3.42 ± 1.31] B (or bits), while the self-information of the target artifacts (or source code) is on average [5.91 ± 0.86] B. This means that the amount of information of the source code is 1.72 bits larger than the amount of information in the set of issues. Now, the mutual information is on average [3.21 ± 1.19] B, the minimum shared entropy is [1.45 ± 1.14] B, and the minimum shared extropy is [0.87 ± 0.54] B.

The loss and noise are both gaussian distributions with a median of 2.53B and 0.11B respectively. The loss is larger than the noise by a range of 2.42B. If we consider that the median of the minimum shared entropy is 1.50B, then the amount of lost information is high. This might indicate that the source code is poorly commented. Furthermore, the noise is barely a bit unit, which indicates that the code is not influenced by an external source of information.

The similarity metrics have a non-standard behaviour. For instance, let’s compare the cosine similarity (for doc2vec) and the WMD_sim (for word2vec). The average value of the cosine is [0.09 ± 0.07], while the value for the WMD_sim is [0.45 ±0.90]. Both similarity distributions are unimodal, which indicates that the binary classification does not exist and both similarities are not overlapping.

Summary: the maximum transmissions of information was around 4.4 bits from issues to source code. If we observe the link {PR-294 ➝ psb_mapping.py}, which corresponds to the minimum MI of 5.5 B in the 99% quantile, then we infer that the 4.4 B of maximum transmission can be improved until reaching an average value of 5.5B. We recommend that software developers implement inspection procedures to refactor documentation in both requirements and source code to enhance mutual information (and MSI).

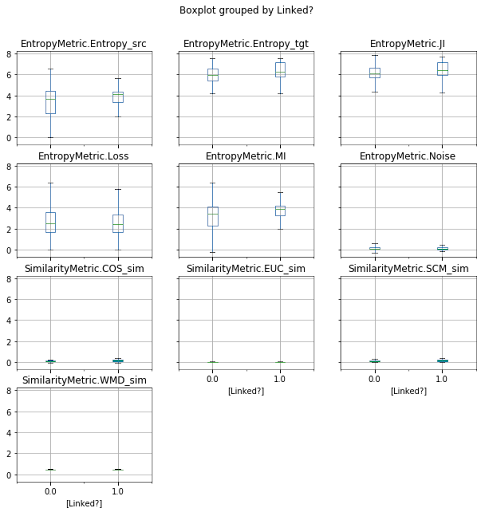

3.2 EDA2: Manifold of Information measures by Ground Truth

Unfortunately, information measures are not being affected by the nature of the traceability. That is, information is independent of whether a link between two artifacts exists or not. Nonetheless all sequence-based artifacts are related somehow (or share some amount of information), this “independent” behaviour is not expected in similarity metrics such as softcosine, euclidean, or word mover’s distance. Neural unsupervised techniques based on skip gram models are unable to binary classify a link. In other words, data do not have encoded the necessary patterns to determine the classification. We need to employ probabilistic models to intervene in the expectation value of a link (see COMET approach) or systematic refactorings on the artifacts.

- Self-Information of source artifacts I(X).

-

Linked [3.80 ± 1.16] B Median: 4.12 B -

Non-Linked [3.41 ± 1.31] B Median: 3.64 B - Interpretation: Confirmed links and non links intervals are overlapping in a large entropy range for the source set. The distance between the medians is around 0.48B. We cannot see any entropy difference between linked and non-linked source artifacts.

-

- Self-Information of target artifacts I(Y).

-

Linked [6.23 ± 0.89] B Median: 6.21 B -

Non-Linked [5.90 ± 0.86] B Median: 5.90 B - Interpretation: Confirmed links and non links intervals are overlapping in a large entropy range for the target set. The distance between the medians is around 0.31B. We cannot see any entropy difference between linked and non-linked source artifacts.

-

- Mutual Information I(X:Y).

-

Linked [3.60 ± 1.06] B Median: 3.85 B -

Non-Linked [3.20 ± 1.19] B Median: 3.39 B - Interpretation: Confirmed links and non links intervals are overlapping in a large mutual information range for both sets. The distance between the medians is around 0.46B. Mutual information does not work as a predictor of links with the given ground truth. We expect high mutual information in confirmed links and low mutual information in non-links.

-

- Information Loss I(X|Y).

-

Linked [2.63 ± 1.33] B Median: 2.46 B -

Non-Linked [2.71 ± 1.35] B Median: 2.53 B - Interpretation: Confirmed links and non links intervals are overlapping in a large entropy loss range for both sets. The distance between the medians is around 0.07B. The loss is basically the same for links and non links. We expect high loss in non-links.

-

- Information Noise I(Y|X).

-

Linked [0.20 ± 0.31] B Median: 0.09 B -

Non-Linked [0.21 ± 0.30] B Median: 0.11 B - Interpretation: Confirmed links and non links intervals are overlapping in a large entropy noise range for both sets. The distance between the medians is around 0.02B. The noise is basically the same for links and non links. We expect high noise in non-links.

-

- Minimum Shared of Information for Entropy.

-

Linked [1.98 ± 1.11] B Median: 2.00 B -

Non-Linked [1.44 ± 1.14] B Median: 1.50 B - Interpretation: The distance between the medians is around 0.5B. We expect high shared information in confirmed links and low shared information in non-links for the entropy.

-

- Minimum Shared of Information for Extropy.

-

Linked [1.07 ± 0.43] B Median: 1.25 B -

Non-Linked [0.86 ± 0.54] B Median: 1.12 B - Interpretation: The distance between the medians is around 0.13B. We expect low shared information in confirmed links and high shared information in non-links for the extropy.

-

Summary: Despite the fact that the amount of information in the source code is larger than the amount of information in the set of issues; the MI, loss, and noise are indistinguishable from confirmed links to non-links. We expect low amounts of mutual information and high amounts of loss and noise for non-related artifacts.

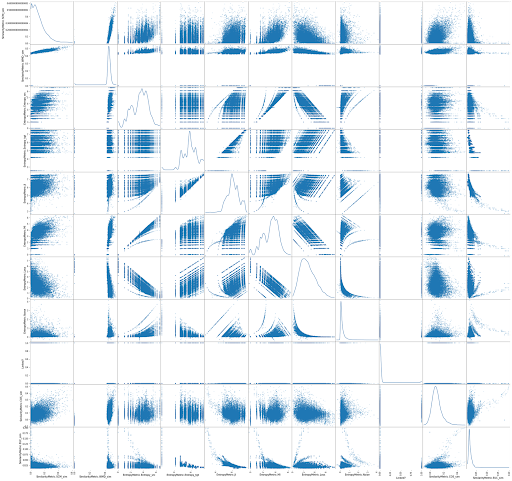

3.3 ED3: Scatter Matrix for Information Measures

Correlations are helpful to explain variables that we are not easily able to describe just by observing their values. Correlations are useful to interpret the causes or detect similar patterns for a given metric. In this case, we want to study similarity variables by correlating them with other similarity variables and information measures (e.g., MI, Loss, Noise, Entropy, etc). The following manifold in Figure 3 depicts all the correlations and distribution of each information variable. We want to highlight that the WMD similarity is mostly positively correlated (~0.74) with other information metrics, while COS similarity has the opposite effect.

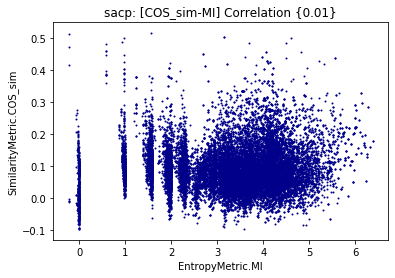

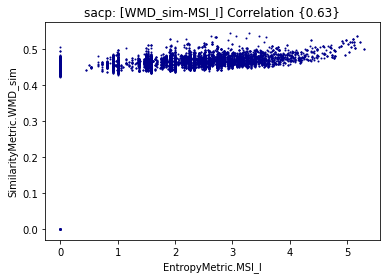

3.4 Mutual Information & Shared Information Entropy and Extropy

This analysis consists of computing a correlation between the distance and entropy. Mutual information is positively correlated with WMD similarity as observed in Figure4. This implies that the larger the amount of shared information, the more similar the artifacts. The previous statement makes sense until we observe that MI is not correlated with the cosine similarity. Is the word vector capturing better semantic relationships than paragraph vectors? Apparently, both approaches are not performing well according to the supervised evaluation.

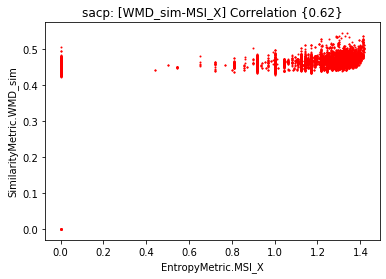

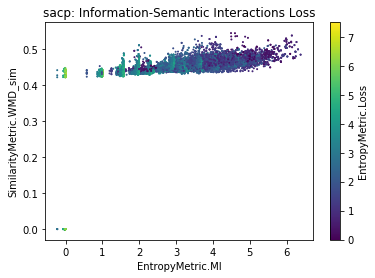

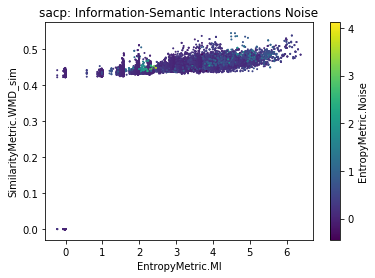

On the other hand, the MSI for entropy is also positively correlated with the WMD as depicted in Figure 5. The trend is expected after observing the correlation with the mutual information. However, the extropy is also positively correlated. Basically, we are showing more evidence that WMD similarity is capturing better semantic relationships among the artifacts.

3.5 Composable Manifolds

The composable manifolds are useful for inspecting a third information variable. In this case, we focused on the loss and noise (see Figure 6). We can observe that the loss is larger when the mutual information and similarity are lower. However, the noise is more dispersed across the mutual information and similarity. We find different clusters of noise in low and larger ranges of MI. These trends indicate that there is some amount of information that was injected in the source code but it is independent from the conceptual similarity of two artifacts.

Summary: Loss entropy is related to low levels of similarity and mutual information. We need to intervene in the datasets to help classify the links by reducing the loss. Such interventions (or refactorings) can occur because developers or stakeholders complete or document artifacts during the software lifecycle.

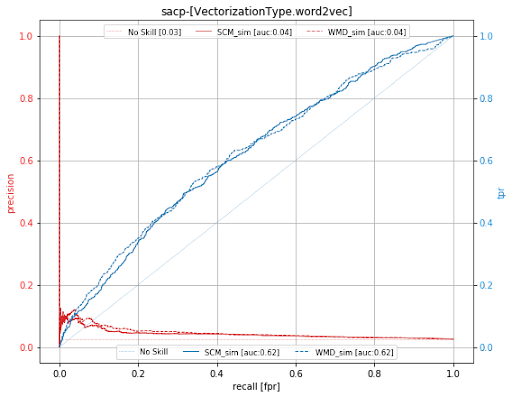

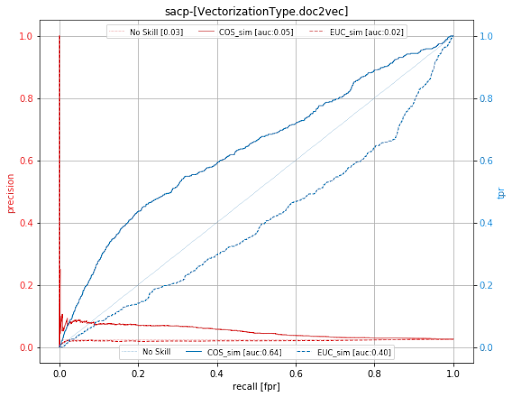

Supervised Evaluation

The supervised evaluation consists of measurements of the accuracy of the link recovery. The link recovery is computed in terms of precision, recall, and AUC. Nevertheless both techniques are not capturing semantic similarity in an efficient way, the skip gram model has a better efficiency than the paragraph distributed model for the XXX dataset. This is not a problem of the unsupervised learning approach but a limitation of the data. The data are insufficient to capture patterns that contribute to the binary classification or traceability generation. If we observe Figure 2, we can explain this behaviour by stating that both WMD_similarity and COS_sim are not different when grouped by ground truth. What is more, the median information in source artifacts is 1.12B, while the median in target artifacts is 3.65. Such a situation created an imbalance of information not allowing unsupervised techniques to capture features from source artifacts. In fact, the median MSI for confirmed links is 2.0, which is quite low considering that the MSI max value is 5.23.

Summary: The set of confirmed links and non-links are extremely imbalanced. Cosine and Soft-Cosine similarities behave better under AUC analysis, which means they actually identify non-links with a minimum effectiveness of 0.62. However, neural unsupervised techniques failed at identifying actual links since the data is not “naturally” partitioned or grouped (see EDA grouped by ground truth).

Some Use Cases

This section shows four information science cases from processing the XXX system. The whole set of experiments and samples can be found in this link.

- Case 0: Self-Information. This study highlights the imbalance of information between the source and target artifacts.

- Case 1: Minimum and maximum loss. This study presents edge cases for the entropy loss. This is useful to detect poorly documented target artifacts.

- Case 2: Minimum and maximum noise. This study presents edge cases for the entropy noise. This is useful to detect poorly documented source artifacts.

- Case 3: Orphan informative links. This study points out a set of informative links that are not found in the ground truth.

Consider the following notation for this section. Down arrows 🠗 represent the minimum entropy value observed. Up arrows 🠕 depict the maximum entropy value observed. Entropy values are given in bit unit (B). Links with value 1.0 are confirmed-links, whereas links with value 0.0 are non-links.

Case Study 0: Self-Information

- Case Study 0.1: Low Entropy Artifacts In some cases, low amounts of information in source artifacts might indicate that pull requests (or requirements) are undocumented. For example, PR with the following IDs have a zero (or minimum) entropy value: PR-241, PR-168, PR-144, PR-128, PR-113, PR-101, and PR-41. Low amounts of information in target artifacts might suggest that the source code is repetitive, undocumented, or empty. For example, these files (<=0.05 quantile) have an entropy less than <= 4.74 B: webex_send_func.py, ipcReport.py, fireException.py, and (of course) __init__.py.

- Case Study 0.2: High Entropy Artifacts In some cases, high amounts of information in a source (and target) artifacts might indicate that the inspected pull request (or source file) has a diverse set of tokens that describe or determine the content of the artifact. In other words, high entropy may indicate the relevance of the artifact. For instance, PR with the following IDs have a max entropy of 6.56: PR-256 and PR-56. While these files (>=0.97 quantile) have an entropy greater than 7.45 B: security_results_push_func.py, binary_scan_func.py, and run_ipcentral_automation.py

- Discussion. Artifacts with low levels of entropy struggle to generate traceability links in view of the fact that unsupervised techniques rely on concise descriptions in natural language. By contrast, high levels of entropy struggle with other conditions like loss or noise. Refactoring operations need to be applied on source and target artifacts to combat the imbalance of information. At least, a semantic idea expressed as a clause is required in both artifacts to guarantee a link. When we preprocess the source code, we are basically transforming the code structure into a sequence structure to extract those clauses. In other words, source code is not treated as a structured language but as a regular text file. The amount of information lost by preprocessing source code as text has not been yet computed.

Case Study 1: MaxMin Loss

- Case Study 1.1: Max Case

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 0.0🠗 B): 241

- PR Content: “Reportbugs”

- Source Code ID (self-entropy 7.50🠕 B): “sacp-python-common/sacp_python_common/security_results_push/security_results_push_func.py”

- Loss: 7.5 B

- Trace Link: non-link

- Case Study 1.2: Min Case

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 6.56🠕 B): 256

- PR Content: “’Parameterize corona hostname This is intended to be a backwards-compatible addition of the ability to set the Corona hostname using a new

--corona-hostnameflag that is not required and defaults to corona.cisco.com. The underlying Corona, Bom, Cve, and Triage classes are also updated in a backwards-compatible way to add the ability to set thecorona_hostnameinit parameter, also with a default value. I tried to follow the pattern I saw in use for thejob_nameandbuild_tagparameters, assuming that this snippet is what will automagically set theself.corona_hostnameattribute:def create_argument_parser(self, **kwargs): ... parser.add_argument( "--corona-hostname", type=str, help="Corona hostname", default="corona.cisco.com" ) ... def run(self): # parse the command line arguments arguments = self.create_argument_parser(description=__doc__).parse_args() # populate the argument values into self for arg in vars(arguments): setattr(self, arg, vars(arguments)[arg]) ...I think I got everything that needs to change, but this is my first work with the module so I'd be happy to step through things on a WebEx with someone if you'd like. I'm not going to document this feature as I don't want to give too many teams the idea to start pipelining builds to Corona staging, but as I've mentioned we need this so we can integrate thebinaryScanstep into our staging sanity test stage so we can catch any API drift before it hits production. Next steps will be to update the container's entrypoint so it knows how to call the binaryScan module with the new flag if it's provided, then to update the binaryScan Groovy to look for this parameter in the config map and pass to the [docker_run and venv_run closures](https://wwwin-github.cisco.com/SACP/sectools-jenkins-lib/blob/master/vars/binaryScan.groovy#L109-L207” - Source Code ID (self-entropy 4.82 B): “sacp-python-common/sacp_python_common/third_party/cve.py”

- Loss: -0.01036

- Trace Link: confirmed-link

- Case Study 1.3: Quantile Loss (>=0.99) for Positive Links In this study, we are just observing the loss 99% quantile for positive links.

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 5.09 B): 193

- PR-Content: “CIC-698: Git pre-commit hook for linting This PR adds pre-commit hooks for python file linting. It accomplishes this by using black, flake8, and isort. Also added in this commit is Pipenv for dependency tracking and virtual environment for development. The changes were ran through the HelloWorld demo build we have, linked here.”

- Source Code ID (self-entropy 2.52🠗 B): sacp-python-common/sacp_python_common/template/__init__.py

- Source Code Content: “import os\r\n\r\nTEMPLATE = os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(__file__))\r\n”

- Loss: 2.76🠕 B

Discussion. Edge cases of loss are useful to detect starting points for a general refactoring in the target documentation. The max case shows us the pull request content is composed just by one word. The tokens that represent this word were not found in the target security_results_push_func.py, which is one of the highest entropy files. Whereas, the min case shows us the pull request has a complete description that was not found in the target. Now, let’s pay attention to the 99% quartile for positive links. The PR-Content cannot be easily found in the source code with low entropy. Even if a software engineer tries to do a manual extraction of links. The relationship is not evident.

Case Study 2: MaxMin Noise

- Case Study 2.1: Max Case

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 6.56🠕): 256

- PR Content: see above

- Source Code ID (self-entropy 2.52🠗): “xxx-python-common/sacp_python_common/template/__init__.py”

- Noise: 4.12 B

- Trace Link: non-link

- Case Study 2.2: Min Case

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 3.38): 213

- PR Content: “’Third Party refactor (#211) * folder * first stage changes * first stage changes * first stage changes * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * stage two changes * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * bd fix + unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unused function * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * unittest * 3rd party refactor * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bdfix * bdfix * bdfix * conflict * BD fusion * bd fusion * bd fusion * bd fusion * bd fusion * Corona class * Corona class * Corona class * Corona class * Corona class * Corona class * Corona class * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * byos tests * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix * bugfix”

- Source Code ID (self-entropy 5.37): “xxx-python-common/setup.py”

- Noise: -0.44 B

- Trace Links: non-link

- Case Study 2.3: Quantile Noise (>=0.99) for Positive Links

- Pull Request ID (self-entropy 0.0🠗): 241

- PR-Content: “Reportbugs”

- Source Code ID (self-entropy 7.48): xxx-python-common/sacp_python_common/third_party/binary_scan_func.py

- Source Code Content: (large file)

- Noise: 7.48🠕

Discussion. Edge cases of noise are useful to detect refactorings in documentation found in the source documentation. Let’s observe the max case, the PR content is really high, but the target artifact is the _init_ file, which is empty. This suggests that the target is not well documented (but in this case makes sense). Something similar happens with the min case. However, this time the PR content is very repetitive and less expressive. Now, a useful case would be one with positive links in the 99% quantile. Here, we can detect that the PR-241 is poorly documented since the noise is around 7.48B, while the target is one of the highest entropy files.

Case Study 3: Orphan Informative Links

This case study introduces orphan informative links or potential links with a high mutual information but with a negative ground truth. For instance, the following 3 links are negative links in the ground truth but they are in the 99% quantile of MI:

{PR-56 ➝ spotbugs/spotbugs.py}: 6.31 B

{PR-56 ➝ third_party/binary_scan_func.py}: 6.38 B

{PR-256 ➝ spotbugs/spotbugs.py}: 6.31 B

Discussion. Orphan links not only exhibit inconsistencies in the ground truth file but also suggest potential positive links independent of the employed unsupervised technique. The previous examples need to be further analyzed to decide if they are actually a link. Otherwise, we need to find an explanation of why they are sharing such an amount of information.

Citation

@misc{palacio2023tracexplainer,

title={Information Theory for Interpreting Software Traceability},

author={David N. Palacio},

year={2023},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.SE}

}